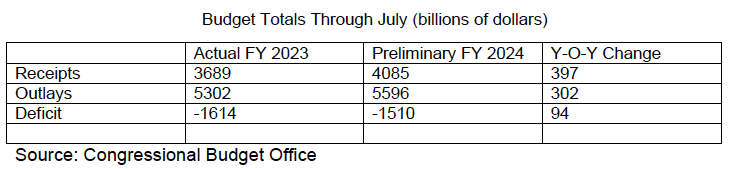

As you can see from the table above, we are on pace for an annual deficit of $2 trillion, give or take a couple of hundred billion. This mismatch between revenue and spending is pretty much as predicted, and nobody seems too bothered by it. Some ritualized denunciations of the growth in the national debt and deficits are appended to speeches lambasting the “mess in Washington” or are trotted out as a casus belli for “taxing the rich,” but in an election even shorter on policy prescriptions than usual, neither party seems interested in presenting actual numbers. This makes tactical sense in an era when detailed policy prescriptions can only hurt a candidate as they give the press and punditry something to analyze; far better to remain vague and anodyne. Budget policy discussions do not go viral on Tik Tok, and specifics on cutting spending and raising taxes can only lose you votes. And so merrily we roll along, comfortably numb to the presence of a large and persistent deficit.

But, you might protest, hasn’t this commentary taken the position that concerns over government funding are overblown? It is true that we are not discomforted by the deficit for the reasons usually given. For example, recently we were the only participants at a fund presentation who didn’t raise their hand when the speaker asked who was worried about the deficit’s effect on interest rates. Most people who bemoan Washington’s unbalanced budget speak of chimeras like foreign buyers’ strikes or unfriendly states dumping Treasuries, of failed debt auctions or a crowding out of private borrowers. They are fond of false analogies—the usual canard compares the government finances to a household budget. We have dealt with these misguided notions in past commentaries; suffice it to say that the US Treasury, with the cooperation of the Federal Reserve Bank, borrows money into existence and, absent either a change in policy or the collapse of the financial system, can continue to do so ad infinitum, the only exogenous threat to this procedure being a weakening of the currency, generally experienced as inflation.

But if we do not fear the collapse of the Treasury’s funding mechanism, why does this commentary continue to harp on the deficit? A fair question, to which we respond with two concerns. The first, outlined last month, is that the growing national debt may someday reach a size which constrains the Federal Reserve’s ability to raise interest rates. While this might sound like an advantage in some quarters, we believe it is not.

Our second concern over the deficit is more abstract and philosophical, although in the long run we feel it is more important. In the past, large US budget deficits have only occurred in response to pressing national crises; World Wars I and II most obviously come to mind, but the response to the economic downturns of the dot com era, the Great Financial Crisis, and the COVID-19 virus as well. Once the challenge had been met, the expectation was that the deficit would be brought back down to pre-crisis levels in a timely fashion.

Now, however, no one in Washington of any party persuasion considers it necessary or even desirable to bring the deficit back down to pre-COVID levels. In our opinion, this is primarily due to the fact that the federal budget has become the source of high margin recurring revenue for large sectors of the American corporate landscape like tech and health care. The Pentagon, law enforcement, and homeland security purchase extensively from the tech sector. These purchases are made with price as a secondary consideration. In health care, where the federal government provides the funds for half of American spending, margins are fat and attempts to cut into them are steadfastly resisted. The only advantage in Medicare Advantage seems to accrue to the insurance industry. We would not be too far off the mark to suggest that continued profit growth depends heavily on the $2 trillion deficit. In short, the federal budget has become a giant piggy bank, a source of funds for large private enterprises rather than an encapsulation of national priorities, not on a one-off basis but as a fundamental grounding for the American asset markets.

One doesn’t need to be a libertarian to see the danger in this.

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual.

The content is developed from sources believed to be providing accurate information.

Securities offered through LPL Financial, member FINRA/SIPC. Investment advice offered through Great Valley Advisor Group, a Registered Investment Advisor. Great Valley Advisor Group and Doylestown Wealth Management, Inc. are separate entities from LPL Financial.