Frozen

Last month we hinted at a paradox lurking in budgetary operations: that having more money to spend slows down the process and provides less. While this is by no means a universal law, it seems to be prevalent in areas like construction and capital equipment. To illustrate, let us consider the Coast Guard’s icebreaker program.

The United States currently operates only two ocean-going icebreakers, the Polar Star (classified as heavy) and the Healy (classified as medium). In the mid 2000’s, the Coast Guard began to push for new vessels, given that the Polar Star and her sister ship the Polar Sea had been placed into service in the 1970’s. The situation became more urgent when the Polar Sea suffered an “engine casualty” in 2010 and was deemed inoperable. It still took three years to initiate the Polar Security Cutter program and four more years until bids were solicited. Finally, in 2019, the contract was awarded, and the first ship was scheduled for a 2024 delivery. As of this date, however, the design work is still ongoing and the scheduled commissioning has been pushed back to 2029, although one can hardly believe that this date will be met.

As you might expect, costs have ballooned along with the delays. The Congressional Budget Office now projects the first icebreaker will cost in the $1.8 billion range (this includes a proportional amount of the design costs). As the schedule slips, this number almost certainly will go higher.

There is another realistic option, however. Finland, a US ally, is a leader in icebreaker construction, and the Finns can build an equivalent ship in two years for an estimated $250 million. Any B-schooler would have no difficulty in choosing most efficient and cost-effective option—indeed, it is doubtful any first-grader would get it wrong. Why then, does the Polar Security Cutter program persist in spending 7 times the going rate for a ship that will be delivered at least three years later?

There are a fair number of reasons, but to our mind they come down to this: politics demand that the vessels be made in the United States, no matter the cost or the delivery slippage. Combined with a distinct lack of urgency from everyone involved, this has led to the dramatically unnecessary spending. One can argue the benefit of building the ships in this country, but the net effect of the Polar Security Cutter program is that a great many people and companies have been and will be paid a great deal of money for doing nothing useful. In a different context (and with a different group of recipients) this state of affairs would have an unwelcome name and be soundly condemned. If we were on the receiving end of the largess we would doubtless see the matter in a different light, but the fact remains that for at least the next five years this country will have only one aging heavy icebreaker which is kept operating by cannibalizing parts from its decrepit sister ship, and the current budget process seems incapable of providing anything better—and no one in a position to make changes is motivated to do so.

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that if the Coast Guard had only had $500 million when it solicited bids in 2017 it would have two icebreakers by now, but because it was able to get $1.8 billion (and counting), it doesn’t have any.

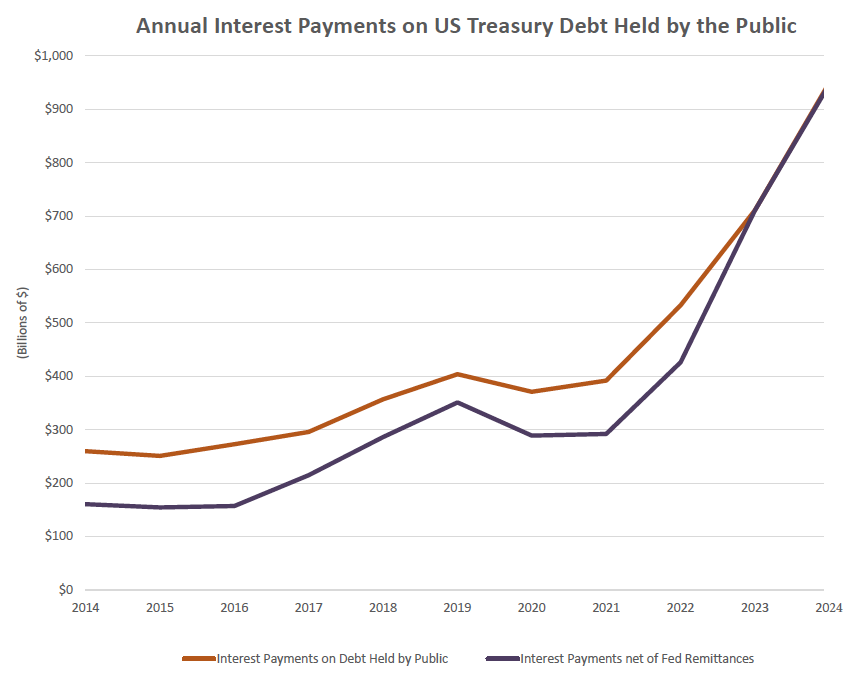

The CBO estimates that the net interest paid on the national debt in the last fiscal year ballooned to $950 billion compared with $710 billion in FY 2022-23. Next year is sure to exceed $1 trillion unless the Fed suddenly returns to a near zero percent overnight rate—something that will not happen without some kind of catastrophe, financial or otherwise.

Most people are aware of the Federal Reserve as a bank for the banks and as the setter of overnight interest rates. In addition to these functions, however, the Fed also holds a large portfolio of Treasury debt, and, since the financial crisis of 2008, mortgage-backed bonds. Since the earnings from this portfolio are remitted to the Treasury (after deducting the Fed’s operating expenses), the central bank has functioned as an investment fund with the effect of reducing the net interest payments–the interest burden, if you will, of the US Treasury. Fed remittances could be substantial; for example, in 2014, they made up almost 40% of the interest the Treasury paid on the debt held by the public.

This flow of money has dried up as the Fed raised interest rates in the last two years, however. As we have discussed in previous commentaries, the Federal Reserve now pays a market rate of interest on bank reserves—that is, the money that banks hold at the Fed. The reasons for this are too long to go into here, but it means that for the last two years the Fed has lost money on its operations, and consequently its remittances to the Treasury have sunk to near zero.

As you can see from the chart, the lack of Fed remittances adds to the US Treasury’s net interest payments at a time when they are already rising due to higher rates. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and may not be invested into directly. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results. The content is developed from sources believed to be providing accurate information.

Securities offered through LPL Financial, member FINRA/SIPC. Investment advice offered through Great Valley Advisor Group, a Registered Investment Advisor. Great Valley Advisor Group and Doylestown Wealth Management, Inc. are separate entities from LPL Financial.