Last month’s commentary elicited a question from a reader — how do we square our distaste for deficits with our insistence that Social Security need not be cut? After all, media stories and commentary bemoaning the deficit almost always conflate this with the Social Security Trust Fund “running out of money” within the next decade unless something is done. The two subjects are lumped together so often that we often overlook how different they are.

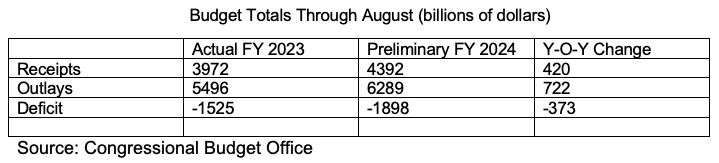

Long-time readers will recall that we have written extensively on the finances of the OSADI program, better known as Social Security. Our suggestion is that the program should simply be funded to provide benefits as promised, and the trillion dollar price tag (which would fix the system for the next 75 years at least) should be allocated over ten years. A $100 billion per year for the next decade would hardly be noticed in the context of a $2 trillion annual deficit.

But why give this “special treatment” to Social Security? Because Social Security is a special kind of program—one which has made specific promises to the vast majority of American workers in return for garnishing their paychecks for throughout their careers. Having dutifully paid into the pension system, we should now not face the cutbacks to the monthly disbursements.

The moral argument for funding Social Security is strong, but as a practical matter, it is one of the few federal programs which can simply be fixed with money. Most of Washington’s other spending is made in pursuit of goals which are poorly defined with ineffective management; in such situations, allocating more money does not move us closer to the stated results and may even perversely defer them. Concern over the deficit has focused policymakers on the size, goals, and time frames of the government’s programs. Without it, the perception of perpetual funding allows spending to flow without much consideration of its efficiency, its goals, and its necessity. There used to be intense fights over budget priorities; nowadays it seems that we drift along allocating money simply because we have in the past.

Spending more money becomes the point of the exercise—proof in the minds of politicians and policymakers that we are “working toward” or “fighting for” whatever part of the mission statement they prefer—be it “securing our borders” or “no child left behind” or the like. No one pays much attention to whether the additional money does in fact secure the border or improve childhood education; one needs only to point out the money being spent to assure one’s listeners of one’s good intentions. The assured largess attracts a legion of consultants, middlemen, and suppliers who become difficult to dislodge.

Again, the danger lies not so much in running deficits than the attitude that spending more money will solve problems by itself. There is no magic level of debt which is the decisive signpost on the road to ruin nor is the government going to “run out of money,” rather, in our current situation, the freedom to spend without effective oversight and management is counterproductive. Social Security is the rare exception to this, and a cash infusion, modest by budget standards, would take care of the underfunding problem for our lifetimes.

Deference

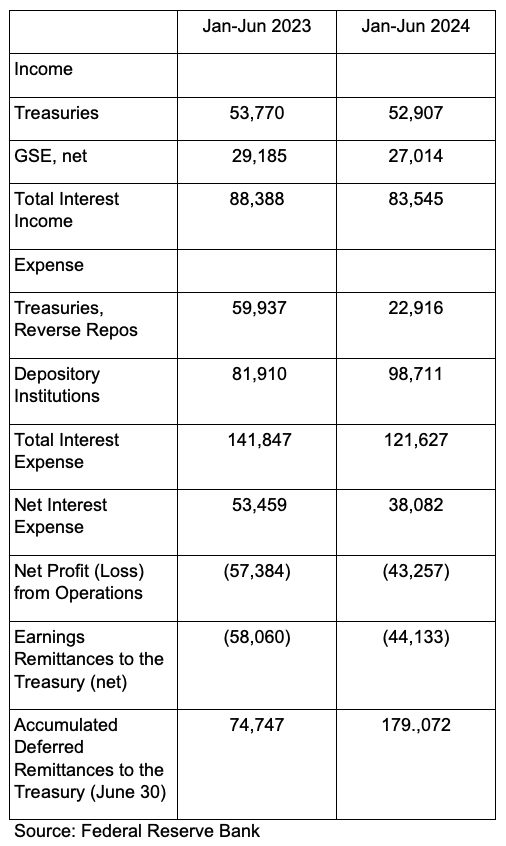

It’s been six months since we checked in on the Federal Reserve’s income statement and balance sheet. As we discussed at that time, the central bank has gotten itself into the unfortunate position of sending out more in interest payments than it received on its portfolio, reversing its customary mode of operation in which it earned a substantial profit on its bond holdings, Since the Fed is legally required to return those payments to the Treasury, this normally has the effect of netting out the interest payments on a quarter to a third of the federal debt. However, because of its Quantitative Easing program, the Fed now finds itself paying interest on reserves — the deposits of its member banks– and operating at a loss as a consequence. (If you would like an explanation of why this is, let me know and I will be happy to go into it in detail.)

As we noted in March, the Fed shoved these operating losses into a line item called “Deferred Remittances to the Treasury” and currently carries them on its books as an asset. That’s not a typo—the central bank paid out $180 billion more in interest than it received and somehow wound up with an asset on its balance sheet. And it did so without a peep from anyone from Washington or Wall Street, as far as we have seen. Sometimes your humble commentator wonders if anyone else is reading the Fed’s accounting statements.

From the Federal Reserve Bank Q2 2023 and 2024 Consolidated Income Statements (in $ millions)

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and may not be invested into directly.

The content is developed from sources believed to be providing accurate information.

Securities offered through LPL Financial, member FINRA/SIPC. Investment advice offered through Great Valley Advisor Group, a Registered Investment Advisor. Great Valley Advisor Group and Doylestown Wealth Management, Inc. are separate entities from LPL Financial.